In many accounts of the Left in Britain there are few references to the work of national minority communists. Certainly in London there was awareness – and occasionally organisational recognition – of significant first generation – Greek Cypriot and Kurdish and Turkish – communist forces operated within their communities and the labour movement. Often in exile, having left political oppression at home, life in Britain saw political action to defend their community from poor social conditions, racist discrimination and harsh exploitative work conditions. Britain’s Black and Ethnic Minority communists have a long history of contributing below the radar to community and workplace struggles. Safely submerged within the broader community movement, communists worked quietly, the low profile reflective of a semi-clandestine nature of the organisation.

There was always a sprinkling of Britain’s foreign-born communists involved in “party activities”, some like Claudia Jones having membership of the CPGB’s International Committee. However the main arena for struggle was within organisations firmly centred in the social base of a national minority community. One of the oldest communist formations, The Association of Indian Communists [AIC] has now taken on an internet presence [ http://indobrit.org/cpb_aic/ ] and signals its alignment to one of the remnants of the CPGB, the Communist Party of Britain.

This open declaration is in marked contrast to its chequered history as a political core operating within the Indian Workers’ Association. Little has been disclosed about the influence and activities of the AIC. The dual membership of both organisations meant that some of the activities of the IWAs should be seen through the prism of AIC membership, and the IWA’s organisational evolution explained by the factional disputes and struggles within the smaller organisation. There was also the added factor that curtailed the contribution of such national minority organisations like the AIC. Nationality based formations reflected the issues and divisions of the ‘Motherland’ and the fractious nature of the IWA is seen in the catalogue of organisational splits and creation of alternative (but similarly named) rivals. The public AIC of today has a different complexion to that that emerged amidst the anti-revisionist struggles of the 1960s that saw distinct, and hostile, organisations operating under similar names. In May 1967 the Association of Indian Communists, Great Britain, Circular No. 2 from T.S. Sahota, Secretary of the Central Executive Committee included a review of the first national conference, Leamington Spa, and a report “of Cde Joshi contained an appraisal of the IWA (Southall)[1]. It was uncompromising: ‘the outstanding common feature of all these groups, despite their internal contradictions, is that they are all anti-communist, opportunist, reactionary stooges of the Indian High Commission, toadies of the Labour Party and hence enemies of the working class and the Indian community.” Such opposition was reciprocated by other IWA towards their former comrades.

Some clarity to the evolution of these separate, sometimes affiliated organisation and the existence of a number of groups called IWA with very different positions, philosophies and functions that came about through a series of splits, is beyond the scope of this posting but can be found an account of the IWA[2] elsewhere. Furthermore the social and cultural nature of the various associations should not be under-estimated, or indeed devalued by a concentration of a political focus that highlights the safeguarding and improvement of immigrant Indians’ conditions of life and work, and their co-operation and unity with the British trade union and labour movement.[3] An indication of the range of work undertaken is evident in the tribute to IWA stalwarth, Manjit Kaur wife of Avtar Jouhl – General Secretary of the IWA. [manjit-kaur] The combination of welfare and campaigning work, in the judgement of IWA (GB) leader, Avtar Jouhl, “enabled it to make its mark as a champion of equality for Indians and other exploited groups in Britain and beyond.”[4]

In the latter half of the twentieth century, the Indian Workers’ Associations became the most important Punjabi associations in Britain and involved mass participation, although it continued to be a predominately male organisation. Although throughout its history since 1938, it encompassed a range of political affiliations, including Akalis, Communists, Congress party members, and members of the British Labour Party, special mention has to be made of the communists as they were the most organised group and able to exert more influence than their numerical strength would suggest.[5] The activity, and almost semi-clandestine profile of Indian Communists in Britain, was largely subsumed and hidden in the broad membership organization of the associations.

Not surprisingly “the spirit of socialism” pervaded the organisation’s attitude to its work and a significant number of the leadership were or had been members of the Communist Party of India. When they arrived in post-war Britain, Indian communists associated themselves with the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). However even when CPGB members, they had their own separate Indian branches and their own officers and could conduct meetings in Punjabi and concentrate on issues and activities of interest to Punjabis.

The Association of Indian Communists was formally constituted at a meeting of the representatives of Indian Communists in Britain held in the presence of Harkishan Singh Surjeet, member of the Polit Bureau of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) on 18th September 1966 in London. Teja Singh Sahota became a founder member of Association of Indian Communist in Britain and was elected to its Central Committee and Secretariat. In 1967 he was elected AIC Secretary.

Sharp disagreements arose from the early 1960s between the IWA (GB) in Birmingham and the IWA Southall. Although the IWA (GB) eventually had branches in Southall and the rest of the Country, it was concentrated in the West Midlands. The tensions within the communists in the IWA was complicated and involved a number of meetings both of the Association of Indian Communists in GB and of the IWA (GB)and the participation of two members of the politburo of the CPI-M. There are different perspectives regarding what happened at these meetings but the outcome was that a further split took place within the IWA (GB) at the Leicester Conference in 1967, with IWA Southall under the leadership of Vishnu Sharma in the South, and IWA (GB) under Prem Singh politically aligned to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and IWA (GB) identified with a pro-Chinese Marxist-Leninist grouping led by Teja Singh Sahota (1925-2008), Jagmohan Joshi (1936-79) and Avtar Jouhl (1937-) in the Midlands. Because this split was of the centralised body it affected all the branches and resulted in two local IWAs existing in most areas.[6]

Sasha Josephides explained,

The communists in Southall IWA supported the CPI while most of the communists in the IWA (GB) aligned themselves with the new party, the CPI-M. As the party in Britain only recognized the CPI, those Indians who sympathised with the CPI-M could not work within the CPGB. They therefore left the CPGB and formed their own Association of Indian Communists in Great Britain in 1965. By 1966 the Indian branches of the CPGB had dissolved.

This division was clearly related to differences both within the AIC and within the IWA on a variety of issues regarding Britain, India and the international scene. In the background was the international factors, not only the polemic within the international communist movement that was influencing positions but also the factionalism within the Party in India. The CPI analyses of the nature of the ruling Indian Congress Party, attitudes towards foreign and internal policies, organisational issues and, decisively, the border dispute with China, were all matters which deepened the rift between left and right. A split in the CPI was formalised in 1965 with the existence of two Indian communist parties; the rightist CPI and the leftist Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPIM). These differences were brought to a head by the Naxalbari uprising in West Bengal where a number of the Naxalbari uprising, although initiated by CPI (M) militants, were not supported by the CPI-M’s leadership. Those Indian communists who were involved in the uprising or sympathetic to it later broke off from the CPI-M to form the CPI-ML.

The AIC/IWA not surprisingly had contact with the wider international ML movement with various Indian revolutionary organisations that were in existence – like those favourable to the Naxalite positions, the Committee of Unity Centre of Communist Revolutionaries of India (ML), the Communist Party of East Bengal (ML) and Indian Peoples Association in North America – and the KPD (ML) in West Germany to name a few who sought correspondence with their co-thinkers in the AIC.

A peal of spring thunder

The Naxalbari Uprising was hailed in Maoist China as a spark which could spread across India. “The Communist Party of China, then the centre for world revolution, hailed the uprising. On June 28, 1967 Radio Peking broadcast:

“A phase of peasants’ armed struggle led by the revolutionaries of the Indian Communist Party has been set up in the countryside in Darjeeling district of West Bengal state of India. This is the front paw of the revolutionary armed struggle launched by the Indian people……”.

Within a week, the July 5th edition of People’s Daily carried an article entitled ‘Spring Thunder over India’ which said: “A peal of spring thunder has crashed over the land of India. Revolutionary peasants in Darjeeling area have risen in rebellion. Under the leadership of a revolutionary group of the Indian Communist Party, a red area of rural revolutionary armed struggle has been established in India….. The Chinese people joyfully applaud this revolutionary storm of the Indian peasants in the Darjeeling area as do all the Marxist-Leninists and revolutionary people of the world.” [7]

Both Indian Workers Association remained concerned with political and social developments in India. The IWA (GB) P Singh has clear links with the CPI-M through the Association of Indian Communists in GB and provides a platform to visiting CPI-M politicians. The other IWA (GB) sympathetic to Naxalite trend, did not have such links with any single party in India. The Joshi-led IWA (GB) campaigned against the repression of political opponents, particularly Indira Gandhi’s government imposition of a State of Emergency between 1975 and 1977, in the Alliance Against Fascist Dictatorship for People’s Democratic India. Demonstrations at the Indian Embassy in London and the publication of leaflets and pamphlets, such as India’s General Elections Are A Fraud, were a regular feature of IWA (GB) activity.[Found here election-fraud-1977 ] In his writing on the situation in India, Harpal Brar argued that India had had a fascist regime since 1947 and that continued regardless of the elections of March 1977. His pamphlet, “Whence Our differences?” was circulated to IWA members only. When Indria Gandhi visited the UK in November 1978 her meetings were accompanied by hundreds of angry demonstrators. Mrs Gandhi had been invited to speak at Southall by IWA (Southall) whose General Secretary Mr Vishnu Sharua was a National Executive member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The protests were initiated by IWA (GB) and supported by the Organisation of Untouchables, the Akali Party, a Sikh religious party and supporters of the CPI(M) and other IWA.[8]

Behind the IWA (GB) analysis and campaigning was an influential Marxist-Leninist perspective that emphasized the links between racism, fascism and imperialism. The Birmingham based pro-Chinese Marxist-Leninist grouping had resolved its own dilemma to the appropriate role in that could be play within the British working class struggles. The Birmingham triumvirate were politically influential producing a study entitled ‘The National Question: The Application of Marxist Analysis to the National Minority Question in Britain’, presented in 1967 as a report to the Association of Indian Communists.

From papers deposited at Birmingham city archives[9], it is clear the Association of Indian Communists had mirror organisational structures to the IWA, with a Central executive Committee and branch committees elected annually and meetings taking place on a regular basis. National conferences were held and notices and letters circulated to the membership. Dual membership of the two organisations was more the rule, many of those who held office in the IWA featured in the leadership of the National IWA as well as the less publicised AIC. Teja Singh Sahota, was addressed in correspondence as the secretary of the Association of Indian Communists Britain (Marxist-Leninist). Prem Singh, was General Secretary of the Association of Indian Communists in Britain, as well as the leading spokesperson in the (other) IWA. The leadership core was a stable and experienced group that oversaw both the IWA and AIC through turbulent times.

Two personalities familiar on the wider anti-revisionist scene in Britain who were representatives of the AIC at meetings and platforms in the late sixties and late seventies were Abhimanyu Manchanda and Harpal Brar. Both were better known for their leadership of explicitly Marxist-Leninist organisations, the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League (RMLL), led by Manchanda, and its off-spring the Association of Communist Workers (ACW) launched in 1969 and led by law lecturer Harpal Brar. Indeed, Brar was for years able to straddle both movements assuming a leadership position and profile as spokesperson for a variety of organisation he would establish or work within.

For the IWA (GB) – and less publicised the AIC – there were varying depths of contact with domestic maoist groups throughout their existence – Communist Unity Association, the British Marxist Leninist Organisation, forerunner of the CPB(ML), Working People’s Party of England, Communist Organisation of Britain, the Revolutionary Communist League of Britain, whose chairman spoke at an memorial for Joshi .

While relations were evident with the emerging anti-revisionist movement in Britain, sharing platforms at meetings, suggestions to incorporate the Marxist-Leninist grouping within a wider anti-revisionist organisation, as with the 1968 Birch founded Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist), were still-born initiatives. The AIC (Britain) Marxist-Leninist did attend the September1977 Marxist-Leninist Consultative meeting held in Birmingham. This gathering of numerous ML groups from throughout Britain (Workers Party of Scotland (ML) attended) for a weekend of debate and discussion resulted in a self-selected Interim Committee. It achieved little progress in securing ML unity , and later dismissed by the largest ML organisation, the RCLB’s chairman Chris Burford as having a “federalist line on party building and its rightist opportunist line on the relationship between revolution in Britain and the international struggle.”[10] Indeed, the question of the relationships between national minority communists as well as those in exile in Britain, like the Kurds and Turkish comrades in the 1970s, to the party-building tasks in Britain, were never resolved in one organisational form.

There was a danger of exaggerated expectations of the Association of Indian Communists because of its association with the IWA. As community-based organisations, when mobilised they could swell the numbers of any rally or march and the leadership provide a political speech pitch perfect , however that large membership did not necessarily exceed the declared objectives to further India’s attempt to achieve independence, to promote social and cultural activities and to foster greater understanding between Indian and British people.

Jagmohan Joshi (1936-79)

Avtar Jouhl was succeeded as General Secretary by Jagmohan Joshi in 1964, who held this position until his death on June 3rd 1979 aged 43 while leading a demonstration against state racism.

“Never let it be said that the first generation of black immigrants played the role of uncle Toms. Far from it. They took to the streets and struck blows against all oppression. Joshi said, “We won’t sit back, we will hit back.”

- Shirley Joshi speaking at a memorial meeting[11]

During his leadership, the national organisation was probably at its most active and radical in terms of its campaigning activities. In Joshi, the IWA (GB) had a charismatic leader, and accomplished poet (under the name of Asar Hoshiarpuri) . delhi-is-not-far-away The Times described Joshi as “uncompromising and thoughtful Maoist industriously working for broad-front multi-racial British militant organisation”. In the late 60s this was partially true: the IWA (GB) remain his prime arena of work and political base.

However there was always a perspective of “United Front” campaigning. Sivanandan refers to Joshi as “the man who had initiated so many of the black working class and community movements of the early years and clarified for us all the lines of race/class struggle”.

The attempt to build militant broad campaigning organisation was seen in the early 1960s Joshi initiated the formation of the Coordinating Committee Against Racial Discrimination (CCARD), a broad based campaigning committee of 26 organisations fronted by Victor Yates, MP for Ladywood, who was the first president. Maurice Ludmer of the Jewish Ex Servicemen’s Association and editor of Searchlight anti-fascist magazine played a significant role, together with academic, Shirley Fossick, who later married Joshi.

In April 1968 he convened the Black People’s Alliance, attracting 50 delegates representing 20 Indian, Caribbean, Pakistanis and African organisations throughout Britain. But such a heady mix of pro-Maoist and Black Power activists proved an unsustainable agenda in the absence of a unifying revolutionary party.

The journalist, Malcolm Southan, described the success of an alliance of black groups to have been largely due to the abilities of Joshi [12] .He was the central figure in the formation of many campaigning groups, an important spokesperson at the time of the ‘wild cat’ strikes in the Midlands foundries and the mobilisation against anti immigration legislation, and he wrote and spoke in many forums, analysing the forms of racism and other political issues.

From 1972 until his death in 1979, Joshi ran a bookshop called ‘Progressive Books and Asian Arts’ on Bristol Road, Birmingham. The bookshop sold Marxist and progressive literature from all over the world as well as Chinese arts and crafts. Members of the IWA (GB) contributed funds for the lease of the shop. The shop was important not only in terms of the role it performed in providing an outlet for distributing progressive literature but also because it enabled important links to be made between members of the IWA, anti-apartheid groups and progressive groups at the University of Birmingham.

One of Joshi’s personal contributions was his instrumental encouragement towards the formation of the Birmingham Communist Association (BCA) in 1975. Paying tribute to his contribution, the BCA said [12] “Comrade Jagmohan ]oshi was known as a determined campaigner against racialism and imperialism and for his support of the struggle of the Indian people for national liberation. He opened many eyes to the realities of oppression in India and other parts of the Third World, and introduced many people to a greater understanding of racialism……

He always emphasised the need to participate in the working class struggle in this country, and to strive to build a communist movement. He struggled against revisionism and never hesitated to denounce the so- called parties of the working class as frauds. At the same time as a mature communist, he understood “who are our enemies” and “who are our friends”, and worked and discussed with progressive people at all levels, always involving as many people as possible in broad front work.”

Campaigning against racism, discrimination and social exclusion

The Indian Workers Association led by Joshi campaigned against discrimination and social exclusion facing Indian and other black and Asian migrants in Britain through poor housing conditions, employment inequalities such as the segregation of facilities in factories where its members worked; the operation of a ‘colour bar’ in employment and education, as well as in shops, public houses, and other leisure facilities; and the restrictions of immigration legislation introduced during the 1960s and 1970s. Under A Jouhal the IWA (GB) opened the Shaheed Udham Singh Welfare Centre in May 1978 at 346 Soho Road, Handsworth. operated an Advice Centre, taking on case work for the local population.

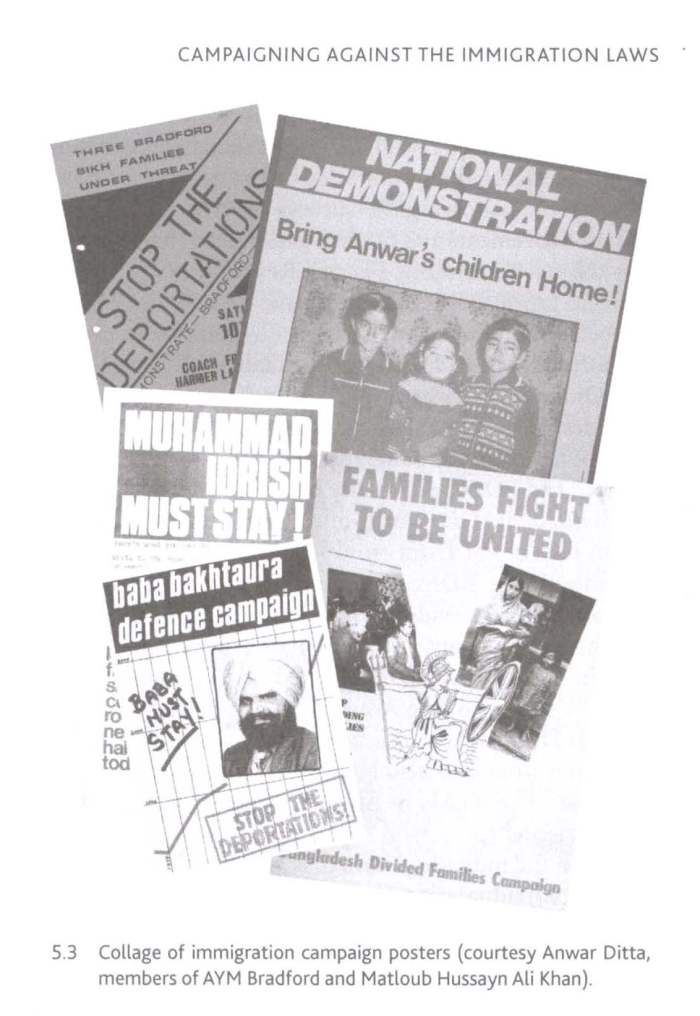

National minority people have been actively organising in defence of their lives and communities and the rise and demise of organisations such as the Coordinating Committee Against Racial Discrimination (CCARD) formed to opposed the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Bill and the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) inaugurated in February 1965. Throughout the 1970s Joshi’s IWA continued to challenge state racism through participation in the Campaign Against Racist Laws (CARL) and the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism [CARF].

Indeed one of the IWA’s main campaigns during the 1960s was against immigration legislation, in particular the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Bill. This bill sought to restrict the entry into Britain of black migrants from Commonwealth countries. The IWA, in conjunction with other bodies such as the West Indian Standing Conference, and the Standing Conference of Pakistan, fought hard against this legislation, putting together a pamphlet entitled Victims Speak and posting it to each Member of Parliament. However, the campaign did not stop the Bill becoming law, and 1962 escalated the politicisation of race as an issue in British politics.

After the passing of race relations legislation in the mid-1960s differences between the different IWAs (reflecting differing Marxist analyses) became more pronounced. In practice, the different IWA groups continued to do similar work, and in some cases even campaigned together in some trade union struggles and against immigration control. Both groups struggled for recognition as the ‘real’ Indian Workers Association during this period.

The emphasis and political orientation of each IWA (GB) was reflected in its publications communicating information on anti-racism, campaigns and social and political issues: the IWA (GB) published many pamphlets also in English, the IWA (GB) of Prem Singh published extensively in the Punjabi newspaper Des Pardes. Pamphlets concerning immigration legislation such as ‘The Victims Speak’ or ‘Smash the Immigration Bill 1971’ were an important part communicating the IWA’s message. Mazdoor (‘The Worker’) the IWA’s first newsletter/ journal was published by the Birmingham branch in 1961 mainly in Punjabi but also with some articles in Urdu, reflecting its wider communal reach. In 1967 Lalkar (‘Challenge’) replaced Mazdoor as the newsletter of the IWA (GB). Avtar Jouhl was appointed editor of ‘Lalkar’ (Challenge). Described by The Times as published in Brussels courtesy of the Pro-Chinese Belgian, Jacques Grippa, 1500 copies are “printed in Punjabi, it has been flown to London at no small expense and sold to Indian immigrants in Britain as part of an effort to convert them to Maoist revolution.” [13]. It was relaunched in 1979 under the editorship of Harpal Brah. Lalkar as a bi-lingual publication in Punjabi and English. Both Mazdoor and Lalkar were primarily political journals, analysing political events from a Marxist-Leninist perspective, but they also focused on news about demonstrations and other IWA activities.

Differences in political perspectives and analysis underlined the split had as much to do with issues relating to politics in Britain. Joshi’s supporters in the IWA (GB) believes that because many white workers have been corrupted into racism, whilst black workers have at the same time become more politicised, both through their experiences of exploitation as well as by their earlier struggles against imperialism, then black workers will often find themselves taking the initiative in workplace struggle, and would then be joined by white workers.

“We feel unity (between black and white) will develop in struggle. This does not in any sense deny the need for black workers to have their own caucuses in every factory and place of work. We do not advocate separate black unions; that would be to play the capitalists game of dividing the working class” [14]

There was a twin track commitment to forming strong trade unions to oppose the erosion of the rights of working people and to fight racism within unions and to organise workers in the sweatshops (mostly-Asian owned) of the Midlands. Support was given to shop floor revolts by Asian workers, such as the strike by Asian workers in 1965 at Courtauld’s Red Scar textile mill in Preston and, in May 1974, Asian workers at the Imperial Typewriter Company[15] in Leicester on strike over unequal bonus payments and discrimination in promotion. The shop stewards committee and union branch refused their support. A few years later the IWA (GB) were very active in support of the Asian women workers at Grunwick photo processing plant in north west London. About Grunwick [16], there is a great deal written and it is celebrated in the UK’s trade union history – even though the strike was lost, the company continued to refuse union recognition and the striking workers were not reinstated. What Grunwick did was generate solidarity actions and support across the wider union movement. [Assessment of grunwick ]

In the 1970 general secretary’s report, Joshi had stated that ‘there can be no question of black power outside of the class struggle’ and above ‘Led by black workers we shall try to find who our friends and who our enemies are. We shall try to unite with the former and fight the latter irrespective of their ethnic origins….for us black power is the establishment of a socialist state in which the workers of our country will take the lead in everything.’ [17]

Fighting racism was considered, by the marxist leaderships within both IWAs, to be inseparable from the creation of a strong working-class movement. However the difference in their two positions was fundamental and led to one group becoming concerned with a black power dimension, forging links with black groups, culminating in the formation of the Black Peoples Alliance, and later there were limited links with the Black Panthers.

The Indian Workers Association (GB) appears to have considered that the Indian Workers Association (Southall) committed to a more traditional class analysis, had an assimilationist philosophy. Harpal Brar, of the Southall branch of the AIC wrote an internal AIC pamphlet “Once Again on the Question of Participation in Bourgeois parliamentary elections and the mistakes of our ‘left comrades’” (May 1978). He had authoured an attack on rivals in the Indian Workers’ Association (Southall) in the 1976 pamphlet “On the Lap-Dogs of Indian fascism: an exposure of the leading clique of the IWA (Southall).”

Such vituperative attacks were not forgotten.

The IWA led by Prem Singh did not attribute a special role to black workers and considered that the initiative for the struggle has to come from the working class as a whole. As an organisation neither group supported any British parties but individual members belonged to the Labour Party and members of each of the IWA (GB) have served as Labour Party councillors.

The Indian Workers Association (Southall) worked with government bodies whereas the Indian Workers Association (GB) actively encouraged Black workers to lead the fight against racism with campaigns and systematic opposition to racist political parties and racist laws and links were actively sought with other national minorities and black power organisations. IWA (GB) under Joshi refused to become involved with state-sponsored groups. They were to become more ambivalent on this issue.

In 1981, the Campaign Against racist Laws saw 20,000 demonstrate against the proposed National Bill. A couple of years later, in 1983, around 4-5,000 were mobilised. The judgement of long-time supporters on the Maoist Left in Britain concluded, “Maggie – out, out, out” was a leading slogan on the march and the general politics seemed to be a reliance on the Labour party to repeal the Immigration and Nationality laws. It confirmed our view that CARL has watered down its politics in an opportunist attempt to get trade union and labour party support. This was shown in the order of the march which was announced as ‘trade unions first’. Black organisations and campaigns against the deportation of individuals were expected to follow.”[18]

In publicising a joint conference of the IWA and the state-funded Commission for Racial Equality, on the Race Relations Act 1976, held in January 1993, Lalkar argued “an active involvement of all citizens will surely force the government to make changes in this act.” Furthermore, it explained, “Our history is part of an historic process of inclusion. We set out to involve our own members to work with other communities in order to improve the life of all our citizens.”

May 1979 saw the publication of a nine–page resignation letter from East London IWA members highlighting the contradictions within the national organisation. It spoke of the frustration at ‘happy family relationship’ within the IWA structures, of the feudal mentality that failed to address weaknesses, that “drinking partners and friendship are more important than political actions and principles”, complaining that no new branch had been formed since 1974 in Derby.

The appeal of the IWA in the 1980s/90s waned. There had been a number of Asian Youth organisations, like the United Black Youth League, that had embarked upon self-organisation by-passing the existing national minority community  organisations. The Birmingham aligned IWA (Bradford) had encouraged the formation of the Indian Progressive Youth Association, however as recorded in Anandi Ramamurthy’s Black Star, Britain’s Asian youth movements took on an independent radical existence in the struggle of working class black communities against racism in Britain in the 1980s [19] Another challenge came from the growth of communal politics in India with religious fundamentalism Hindu-based parties mirrored in Britain and the rise of forces promoting Sikh separation hostile to the IWAs.

organisations. The Birmingham aligned IWA (Bradford) had encouraged the formation of the Indian Progressive Youth Association, however as recorded in Anandi Ramamurthy’s Black Star, Britain’s Asian youth movements took on an independent radical existence in the struggle of working class black communities against racism in Britain in the 1980s [19] Another challenge came from the growth of communal politics in India with religious fundamentalism Hindu-based parties mirrored in Britain and the rise of forces promoting Sikh separation hostile to the IWAs.

Opposition to US imperialism was vocally matched in the IWA (GB) by condemnation of the actions of the Soviet Union, a position reflecting an anti-revisionist position and support for China’s foreign policy opposition to, what had been described since 1968 as, Soviet Social imperialism. The General Secretary of the IWA (GB), Jagmohan Joshi was well known to the Marxist-Leninist movement as a staunch anti-revisionist: “Comrade Joshi fought for Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought against revisionist and Trotskyite distortions of Marxism. He upheld the People’s Republic of China as a great beacon of socialism and supported the three worlds theory.” [20]

The IWA (GB) had an established record of its support for campaigns on international issues such as the US war on Vietnam and later against the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1979 issuing English language leaflets.

Joshi played an important role in the work of building support for the people of Kampuchea, speaking to about 200 at a picket organised outside the Vietnamese London embassy in February 1979. Joshi said that the picket was but the first step in building a might campaign in support of the Kampuchea people which the IWA was determined to do. [21]

At an earlier day of action and solidarity on February 3rd, an unnamed speaker from the AIC (Britain) Marxist-Leninist was reported to have observe that “Marxist-Leninists had tended to overlook the negative aspects of Vietnamese policy, such as their support of the fascist Indira Gandhi’s regime in India and of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.”[22]

This AIC opposition to Soviet foreign policy was expressed through the international positions taken by the IWA (GB) in support of national self-determination and independence. In March 1980, the IWA (GB) convened a conference on Afghanistan, where T.S. Sahota argued,

“It is high time that all those who oppose the Soviet Social imperialist aggression on Afghanistan, a third world country, and a neutral country, take action to support the Afghan people. As Indians we have a special duty because that aggression is clearly connected with the policy of Soviet social-imperialism in the Indian sub-continent.”[23] This was a minority position of the left in Britain as other speakers against both the superpowers included the Bangladesh Workers’ Association, the Revolutionary Communist League of Britain and the Communist Workers’ Movement.

At Digbeth town Hall the 1982 National Conferences of the AIC, in common with the rest of the maoist movement internationally, saw discussion on the Chinese foreign policy strategy, the theory of three worlds, and the dangers of American and Soviet imperialism and the developments in India. While the domestic focus was on the economic crisis and opposition to Thatcher’s monetarist policies.

However no organisation was immune to the change geo-political realities as the decade progressed that clear political identification became less of a defining feature of the IWA (GB) as changes in China and the Gorbachev era ushered in the disintegration of the Soviet Union and collapse of its ruling party. In May 1986 T.S. Sahota had reported to the AIC National Conference on the changes in the international situation at the IWA (GB)’s welfare centre in Soho Road Birmingham.

The context of the Cold War victory for the West and weakening of the influence and appeal of Marxism towards the end of the last century also had its effect. While competing for community leadership and simultaneously fighting the same fight, the dissolution of international issues that forced their divorce, an attitude of putting the past behind them and strengthening the existing forces, saw movement towards the merging of the IWA into one organisation in February 1991. The shared campaigning between the different IWA saw co-ordination between the two organisation. For instance, in the late 1980s the joint chairperson of the Campaign Against Racist Laws were Prem Singh and Harpal Brar. Given the changes in circumstances, a Co-Ordinating Committee of five representatives of each IWA (that included Brar) was established in November 1989. The two IWAs held a unity conference in June 1990 with the National merger conference taking place on February 16/17th 1991 in Birmingham. Teja Sahota led the IWAGB merger along with Prem Singh Pardesi of IWAGB. Avtar Singh Jouhl, from the “Midlands wing” later became General Secretary of the Indian Workers’ Association (GB). Prem Singh was elected president of the united IWA that claimed 14 branches with a membership of 20,000.

The ability to distinguish and attribute actions and ideas between the IWA and the AIC had always been difficult given the entangled nature of the dual membership and AIC members’ leadership roles. The first National Conference of the united IWA (GB) took place in Woolwich, south east London in June 1993. Under Brar’s control of Lalkar, the accountability between the IWA and essentially its publication became tenuous. Increasingly Lalkar became both an English-language publication, and much more reflective of Brar’s own political positions.[24] Reports of meetings would list speakers like Ludo Martens, President of the Workers Party of Belgium and Adolfo Olaechea of the Comite Sol Peru, and statements issued by the Socialist Labour Party (whilst he was a member) would be reproduced, and news from China and North Korea would have prominences in its pages. There were polemical articles attacking others’ politics e.g. on the Independent Working Class Association (Lalkar May/June 1996) or on the Anti-Racist Alliance’s bourgeois nationalism (Lalkar Oct/Nov 1993). Alongside the reports on anti-deportation and workplace struggles like the Bunsall strikers, there was the more explicit coverage of communist and radical campaigns and meetings. The flavour of the “community paper” was more anti-imperialist orientated, its internationalist outlook was less the IWA – or even the majority of the AIC – and more Brar’s own.

Besides the public criticism of the East London IWA branch, evidence of lukewarm support and passive resistance to the Brar-published Lalkar from within the IWA membership can be seen in the letters that Harpal Brar wrote to Avtar Jouhl discussing the attitude of many branches towards the distribution and collection of payments for the paper.[25] His need to emphasis the need for members to actively support the publication is indicative of the absence of such support.

The coming together of communists from each IWA tradition in the Association of Indian Communists (AIC) saw a political “healing” of the wounds that had divided it. References to the AIC began to appear in Lalkar: in 1993 Teja Singh Sahota spoke at a commemoration rally on Shapurji Saklatvara, Indian communist MP for Battersea North in the 1920s.[26] However it was an AIC that did not include all; The IWA cut its ties with Lalkar in 1992 when members of the executive committee affiliated to CPI(M) objected to an article’s mild criticism of China’s market socialism. Brar treated Lalkar as a personal publishing vehicle and maintained its existence as an independent Marxist-Leninist journal.

The CPGB (ML) explained its perspective when it criticised the AIC’s ally, the Communist Party of Britain.[27] The CPB had described the CPGB (ML) in a report to an international audience in these terms.

“The leadership of the CPGB-ML has its political origins in a ‘Naxalite’ trend in the Indian Workers Association in Britain. The predominant trend in the IWA is led by the Association of Indian Communists in Britain, affiliated to the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Between 1991 and 2004, the Association of Indian Communists tried to maintain unity with the Naxalites. This proved difficult because a Naxalite branch insisted on maintaining its own publication, Lalkar, edited by Harpal Brar, and projecting its own rather than IWA policies, by, for example, denouncing the reforms undertaken by the Communist Party of China and welcoming India’s nuclear tests.

“In 2001, Lalkar applauded the September 11 attacks. The thousands of workers who died in the Twin Towers were all dismissed as ‘bankers’ and ‘stockbrokers’. All Communists, socialists and progressives who disagreed with this position were accused of siding with imperialism (Lalkar, November/December 2001). In 2004, the overwhelming majority of the IWA re-established that organisation without those who published Lalkar. Those excluded today lead the CPGB-ML.”

In reply, the CPGB-ML countered:

“Space and time do not allow us to deal now with these questions of history. We shall, however, say this: It is not true that the leadership of CPGB-ML has its origins in a ‘Naxalite’ trend in the IWA, as is the assertion of the CPB. The political origins of the CPGB-ML’s leadership lie in the trend represented by the Comintern throughout its existence – a trend the CPGB followed faithfully during that entire period. In the leadership of the CPGB-ML there are only two Indians, and they by no means represents the ‘Naxalite’ trend. The CPB’s assertion to the contrary is a product of its fevered imagination.

….

It is not true that it became impossible to maintain unity in the IWA because, according to the CPB, a Naxalite branch insisted on maintaining its own publication, Lalkar, edited by Harpal Brar, and projecting its own policies rather than those of the IWA. This assertion too is the work of the not inconsiderably fertile imagination of the CPB. For one thing, there was no ‘Naxalite’ branch; all the branches of the IWA had a common membership. Second, no branch had a paper of its own. When the two IWAs were united in 1991, Lalkar, which was the organ of that IWA which had no political ties with the CPM, became at the unity conference the organ of the united IWA and continued to be so for several years. The problems with the paper did not arise because the alleged, but actually non-existent, ‘Naxalite’ branch insisted on projecting its own rather than IWA policies. In fact, the boot was on the other foot. It was the CPM leadership, and its followers in the IWA, who wanted Lalkar to represent and reflect CPM policy rather than that of the IWA – a workers’ organisation functioning in Britain.

As to the examples of Lalkar’s alleged deviation from the line of the IWA, the matters stand as follows. When India (and a few days later Pakistan) conducted nuclear tests, the Executive Committee of the IWA (the majority of whom were people with very close ties to the CPM) unanimously passed a resolution in support of these tests. Subsequently, at the behest of the leadership of the CPM, the latter’s followers demanded the rescission of this resolution. It is clear that it was a foreign party’s interference in the internal affairs of the IWA which was the source of troubles in the latter – not Lalkar failing to reflect IWA policy.”

_________________

The pretext was widely regarded to push Brar successfully away from the organisation. The antagonisms that had accompanied Brar’s long involvement since the 1960s was not restricted to his political opponents. In the late 70s, the politically active East London IWA branch had been very dismissive of Harpal Brar being allowed back into membership of IWA, and appointment as National Organiser of the IWA (GB) and editor of the monthly publication Lalkar.

In the post unity period, Harpal Brar retained an independent political existence of the IWA.

There was the fleeting episode when the AIC published a “Statement of Aims”[28] with the Association of Communist Workers as a basis for drawing together Marxist-Leninists with the aim of forming a “genuinely revolutionary Communist Party”. Obviously the shadow of Brar lay behind the statement:

“The party shall defend the gains of October and refute all slanders against the undisputed correct leadership of the CPSU during the period of socialist construction.”

The orthodoxies of Marxism-Leninism (and Stalinist) politics were defended. Brar’s entire anti-revisionist career was rooted in the defence of Stalin. Apart from the contemporary references to the struggle of the Irish people for national self-determination” it was a document that could have been drafted in the 1940s. In 1991, Harpal Brar was a founder member and became chair of the Stalin Society. His writings marks Brar as an unapologetic admirer of Stalin.

The Association of Indian Communists and the Association of Communist Workers – two organisation with Brar in their leadership – took the decision to disband in 1996 and merge into a single organisation called the Association of Communists GB. Ella Rule, long-time associate of Brar’s, was the secretary of the AoC , whose membership went beyond Punjabi males. However, within a month of its foundation, Avtar Jouhl and others left the group due to (it should be stated long existing) ideological differences in February 1997.

The independent existence of the AoC became murky and less obvious when Brar and followers then joined the Socialist Labour Party. Founded in May 1996, the re-establishment (the original Socialist Labour Party, was formed in 1903) of the party, by miner leader, Arthur Scargill, came after Tony Blair’s ‘New’ Labour abandoned its Clause IV symbolic of commitment to progressive change for socialism in Britain. The principles of the SLP are summarised in clause four of its constitution, to ‘secure for the people a full return’ for the wealth and services they generate. In March 1997 the AoC had agreed to support Socialist Labour Party candidates at the General Election. Harpal Brar stood for the SLP in Ealing South finishing fourth with 2,107 votes. He stood again in 2001 and received 921 votes. Brar was equally unsuccessful in European Parliamentary and London Assembly elections.

Brar and his comrades worked to bring what they described as an Anti-Revisionist Marxist-Leninist programme to the SLP, but were eventually expelled seven years later.

In May 2004, Brar was among 13 expelled from the Socialist Labour Party after simmering and open conflict as party leader Arthur Scargill opposed calls for “greater links with the Workers’ Party of Korea”. In July at the Saklatvala Hall in Southall, Harpal Brar was founder-Chairman of the Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist) . Lalkar continued to be published as an anti-imperialist journal, co-existent with Proletarian the bi-monthly journal of the CPGB-ML . [29]

In its heyday the IWA (GB) was able, in its time, to organise demonstrations of tens and hundreds of thousands of workers, and regularly held meetings of 4-5,000 members and supporters, throughout the country. Harpal Brar, reflecting on the history of the IWA (GB) as the Greenwich & Bexleyheath branch celebrated the 50th anniversary of its founding, observed: “Guided by the IWA, the Indian community took a stand against black separatism and took its stand on the communality of interests of the working class. We mobilised to prevent the National Front from holding an ‘Election Rally’ in Southall in 1979, where the police defended the racists, beat hundreds of demonstrators, and murdered the anti-racist campaigner, a teacher from New Zealand, Blair Peach.”[30]

The IWA (GB) had to its record a long list of case work, welfare and social work, campaigning against state racism, miscarriages of justice and racist violence. It had provided platforms from those denied a voice such as Gerry Adams M.P. under a broadcast ban from British TV, and contingents of IWA members demonstrated in support of the striking miners, against communalism in India and in solidarity with Vietnam and later Cuba. The driving force behind much of this visible radicalism was the lesser known work of Indian born communists who made their home in Britain.

APPENDIX

In one of their pamphlets the IWA set out the following position on imperialism and racism which relies on Marxist and Marxist Leninist analysis. This is a precis of the relevant parts: because of the system of imperialism it was possible for the bourgeoisie of certain Western countries through the superexploitation of the colonised peoples to make super-profits. A part of these profits they used to ‘bribe their own workers’ in order ‘to create something like an alliance … between the workers of the given nation and their capitalists against the other countries’. With the crisis in imperialism, and the attendant need to reduce the wage bill through wage cuts and redundancies in order to remain competitive, its necessary to convince the working class that it

is the black immigrants who are bringing about the deterioration in their living conditions. The task of doing this belongs to the fascists and it is

‘relatively easy for them to spread racialism because over the centuries racist propaganda has been implanted in the minds of the working class by the colonialists and the imperialists in order to maintain the super-exploitation and plunder of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America. The anti-black propaganda of the fascists is not an end in itself but a means to an end; the end is, through creating divisions, to smash the working class movement and its organisations with a view to serving the interests of state-monopoly capital.(‘Smash Racialism and Fascism’ July 1976).

The IWA (GB) therefore consider the task of fighting racism to be inseparable from the creation of a strong united working class movement. Because of this, as well as organising around specific campaigns to do with racial discrimination of every kind, the IWA has put much of its effort into organising within the labour movement.

Although the IWA consider the labour movement to be central to fighting racism since they see racism in class terms, at the same time they recognise that many working class white people are racists and consider this to obscure the class nature of racism. Because many white workers have been corrupted and brainwashed as described above and because black workers, through their struggle against imperialism in their own countries and their double exploitation in this country have become more aware, black workers must take up the initiative of fighting the enemy, the capitalist class, not only for themselves but also for white workers. Many white workers would join them in this struggle.

The IWA also recognize that black people who are not workers are nevertheless the victims of racism and must not be excluded from the struggle but consider the black workers to be central (Report of the General Secretary 1970). So, for the IWA, black workers, because of their particular history and class position, are the group destined to lead the fight against racism and therefore black workers have to be organised and united. They also believe that this has to take place within the context of the labour movement because although the initiative for the struggle rests with black workers, success depends on white workers uniting with them.

They are therefore strong trade unionists and also welcome alliances with all other multi-racial, progressive groups.

Source: Josephides, Sasha (1981) Towards a History of the Indian Workers’ Association

Footnotes

[1] Their own assessment of their history can be found here iwa_southall_booklet

[2] Sasha Josephides’ (1981) “Towards a History of the Indian Workers’ Association” Research Paper in Ethnic Relations No.18, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick.

[3] For example the most apolitical cultural association is making a political point and claiming certain types of rights when it arranges a procession or a festival in the streets of London in order to celebrate a religious or cultural event.

Equally, advice centres and welfare groups although their primary function is to make sure that people know and get their rights in such areas as housing, social services and citizenship status, they necessarily become involved in political campaigns against the possible erosion of such rights and in struggles which aim to change laws which are seen as harming their clients.

[4] Avtar Jouhl’s weblog: https://iwagb.wordpress.com/

[5] Unsubstantiated anecdotal suggestions puts membership in the two hundreds.

[6] This situation continued until 1991 when the two ‘wings’ of IWA GB reunited in one organisation.

[7] 30 years of Naxalbari — An Epic of Heroic Struggle and Sacrifice http://www.bannedthought.net/India/PeoplesMarch/PM1999-2006/publications/30%20years/part1.htm

[8] ‘Gandhi’s Visit – Protesters denounce Fascism. Class Struggle Vol.2 No.20 Nov 30-Dec 14 1978

[9] The papers of Avtar Jouhl and the Indian Workers Association 1956-2005

[10] Letter dated 28th September 1979 [Private archive] see: On the Birmingham Conference https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/uk.hightide/cwmletter2.htm

[11] Class Struggle Vol.4 No.13 June 1980

[12] The Sun, January 11th 1969

[12] The BCA was eventually to merge with the RCLB. Class Struggle May 29th to June 11 1980 (Vol. 4. No.11)

[13] The Times News team (1968) The Black Man in Search of Power .London: Nelson :156

[14] Report of the General Secretary, IWA (GB) J.Joshi, 1970: quoted in Josephides 1981: 119. Towards a History of the Indian Workers’ Association. Research Paper in Ethnic Relations No.18, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick.

[15] https://hatfulofhistory.wordpress.com/2014/06/18/before-the-unity-of-grunwick-40-years-since-the-imperial-typewriters-strike/

[16] http://www.redpepper.org.uk/biting-lions-remembering-the-grunwick-strike-40-years-on/

[17] Report of the General Secretary, IWA (GB) J.Joshi, 1970:, quoted in Josephides 1981

[18] RCLB, Anti-Racist, Anti-Fascist Internal Bulletin. April 1983. Private archive

[19] Ramamurthy , Anandi (2013) Black Star, Britain’s Asian Youth Movements. London: Pluto Press

[20] Class struggle Vol.3 No.12 June 14-27,1979 p4

[21] New Age, newspaper of the Communist Workers Movement, No.10 March 1979

[22] ditto

[23] Class Struggle Vol 14 No.7 April 1980 p6

24] Harpal Brar self-published a number of books reflecting his political analysis: Social democracy – the enemy within, Perestrokia – the complete collapse of revisionism and Trotskyism or Leninism. See http://www.cpgb-ml.org/index.php?secName=books

[25] MS 2142/12/A/1/4/12 Correspondence and Campaign files 1978-1984

[26] https://www.marxists.org/archive/saklatvala/index.htm

[27] CPGB-ML’s reply to the lies and slanders of the CPB, Issued on: 04 December 2008 http://www.cpgb-ml.org/index.php?secName=statements&subName=display&statementId=16

[28] “Communist Action” No.9 February 1996

[29] Richards, Sam (2013) The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience. Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/uk.firstwave/uk-maoism.pdf

[30] https://redyouth.org/2015/09/09/indian-workers-in-britain-50th-anniversary-of-the-iwa-gb/#more-3707